Training. Drills. PMS. PQS. Attention to detail.

Do you do just the minimum, or do you ask for extra time to get it better and better? Do you train and inspect hard? How many times have you gone through different scenarios with your crew?

Do all your watch standers know how critical their position and responsibility is? From the OOD to the YN3 on the 50cal.; do they appreciate that they are as important as the Commanding Officer?

Discipline. Discipline and obedience in the time of stress, strain, and unimaginable threat to life an honor. Have you and your crew's training been built to refine and demonstrate those qualities? How do you address shortcomings? Are your Chiefs and First Class focused, demanding, masters of their team and duties?

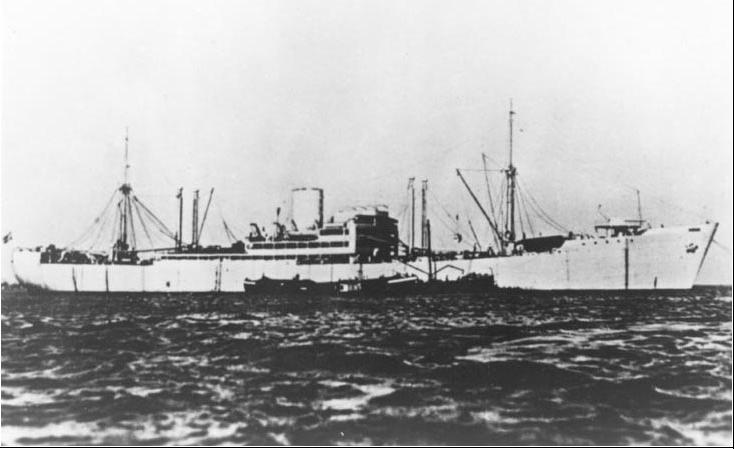

As the Sydney approached the starboard beam of the larger Kormoran, the cruiser used a daytime searchlight to flash the signal “NNJ,” the maritime code ordering the merchant ship to identify herself. After a delay, the Kormoran ran up the signal flags of the Dutch vessel Straat Malaaka, although their location ahead of the freighter’s single large funnel purposefully made it difficult for the Sydney’s spotters to read. The warship requested the freighter to re-position the flags, and as German crew slowly complied, the distance between the two ships, still sailing due west, shrank to a mile.That is why we have standards. That is why we have qualifications. That is why we should demand excellence and discipline. Are your standards and expectation focused for the same reasons as Fregattenkapitän (Commander) Theodor Detmers? An epic story.

“Where bound” came the second signal flashed by the Sydney. “Batavia” was the reply from the Kormoran, indicating the capital of the Dutch colony of Java lying over a thousand miles to the north.

Aboard the German raider, Detmers and the bridge staff watched the exchange of signals anxiously and urged the enemy cruiser to sail away and leave them alone. Their fear rose when they saw the Sydney’s crew prepare to launch the spotter plane from the amidships catapult. The plane, once airborne, would easily spot the hundreds of naval mines strewn about the Kormoran’s high deck, giving away its identity as a raider. But the launch crew apparently received new orders and returned the plane to its storage position.

According to the recollections of Heinz Messerschmidt, a 26-year-old lieutenant commander aboard the Kormoran at the time, Detmers turned to his officers and reassured them again, “Ah, it's tea time on board. They'll probably just ask us where we are going and what cargo and then let us go on.”

By luck and guile the Kormoran had survived for almost a year by preying on isolated Allied merchant ships. But this was its first encounter with a warship brandishing guns of equal firepower. Still playing on its disguise as a helpless merchantman, the Kormoran’s radio operator began broadcasting the alert signal “QQQQ” meaning “suspicious ship sighted.” The anxious signal likely confused the Sydney, whose radio operator would have received the transmission, as did a wireless station 150-miles away in the Australian coastal town of Geraldton.

As the parley continued, the distance between the two ships shrank to less than a mile. Lookouts on the Sydney scanned the freighter for suspicious markings or signs of weapons.

But carefully concealed behind special screens and tarps on the Kormoran’s decks was an arsenal of naval guns, torpedo tubes, and anti-tank guns, all manned, loaded, and trained on the unaware cruiser. Later investigations would attempt to determine why Captain Burnett approached so closely to the Kormoran, or if he was lured into false sense of security.Although both ships possessed guns of similar caliber, the Sydney’s fire control system and experienced turret crews only would be an advantage at longer ranges. Whether by inexperience or trickery, the Sydney’s vulnerable position would soon turn perilous. Over an hour after the cruiser first sighted the freighter on the horizon and gave chase, Burnett ordered the Sydney to flash the signal “1K”–one half of the secret Allied call sign for the Straat Maalaka—across the short gap between the ships. The actual Dutch freighter of that name had a codebook with the corresponding two-letter response. The Kormoran did not. Detmers realized that the time for hiding was over. He ordered the Dutch flag taken down and the German naval ensign run up the mast as the camouflage screens fell away to reveal the line of gun barrels trained on the Sydney. The Kormoran’s 5.9-inch guns fired first, while the rapid-fire anti-tank and machine guns opened up on the officers visible on the cruiser’s bridge. It was shortly after half past five in the afternoon.

The first two 5.9-inch salvos from the Kormoran missed the Sydney, according to reports from the German gunners. But the third volley crashed into the bridge and gun director tower, crippling the cruiser’s ability to return accurate fire just seconds into the battle.

Meanwhile, the raider’s anti-tank and machine guns raked the Sydney’s bridge, presumably killing or wounding many of the officers standing there. Other guns sprayed the exposed portside 4-inch gun mounts and torpedo tubes, preventing their crews from manning them. According to German witnesses, the gap between the two ships was between 1,000 and 1,500 yards—a distance more appropriate for the muzzle-loading cannons of Trafalgar than the rapid-fire guns and high explosive shells of the Second World War.

The Sydney’s first response was a salvo of 6-inch rounds that passed over the now exposed raider. However, the next shells from the Kormoran smashed into the cruiser’s forward “A” and “B” turrets and put them out of action. Another German shell exploded the spotter plane amidships, spilling burning aviation fuel over the decks and black smoke billowing into the sky. Sydney’s “X” and “Y” turrets located in the rear of the ship continued to fire under local control for a few more minutes, but only the crew of “X” achieved hits, sending three rounds into the high-sided freighter. One shell struck amidships, and another punched into the engine room. But the third shell tore through the raider’s funnel, severing the oil warming lines and sending burning fluids cascading down into the motor room to ignite a major fire.

At about this time the Kormoran reportedly launched two torpedoes; at least one struck the Sydney between the mangled “A” and “B” turrets tearing a huge gash in the bow and igniting even more fires. Locked together like two wavering boxers, the warships exchanged constant blows that crippled them both within a few minutes. A storm of shells swept across the water as impacting rounds blossomed into fireballs and pillars of smoke from burning fuel climbed into the evening sky.

Fifteen minutes after firing began, the stricken Sydney made a sudden turn to port, passing close behind the Kormoran and allowing the raider’s rear guns to engage the previously sheltered starboard side of the cruiser. But the Sydney’s turn also permitted her crew to launch a spread of four torpedoes at the raider, all of which missed.

By this time the fires in the Kormoran’s engine room had spread to destroy the machinery, causing the freighter to stop in the water. The Sydney limped slowly away to the south still under fire, down severely at the bow and burning ferociously. Around six o’clock the now immobile Kormoran loosed a final torpedo from an underwater tube at the fleeing Sydney that apparently missed. The 5.9-inch guns on the raider continued to engage the cruiser for another half hour as the range increased and darkness fell. The Germans’ last view of the Sydney came a few hours after sunset—a burning glow on the distant southern horizon that slowly flickered and faded away.

Detmers soon realized that the Kormoran’s uncontrollable fires threatened the hundreds of volatile mines stored on the deck. He ordered his crew to set scuttling charges and abandon ship. Without panicking, the German crew launched lifeboats and watched as the charges detonated along the ship’s keel shortly after midnight, sinking the Kormoran on her 352nd continuous day at sea.

Of the raiders crew of 397 officers and men, 317 survivors reached the Australian coast over the next few days. And in an outcome that has fueled controversy ever since, neither the Sydney, nor her crew of 645 officers and men, were ever seen again.

BZ to ewok40k for pointing out that KORMORAN has been found, and as Matt tells us, the SYDNEY has been found as well.

12 comments:

lol i actually meant the other HMAS Sidney meeting untimely end at the hands of the Kormoran in 1941...

and meant the context for todays warships meeting disguised firepower (Somalia, cough, cough...)

now imagine LCS, our porch hate pet, stopping to search small freighter or large fishing boat off the somali coast... will it be "optimally" manned? will it be ready for the kind of damage short range firefight incurs? will the crew be able to fight AND do the damage control at the same time?

ponder...

Reading the RAN report on the wrecks and the battle damage sustained should send chills up the spine of anyone who goes/went to sea.

You fight like you train. You hear this over and over and over, and yet at their own peril and that of their crews, some people just choose to ignore this sound, timeless advice. You are not put in charge to be liked, you are put in charge to lead and prevail. You don't have to be a pr*ck,, but you have to be clear, firm and set an example that others want to follow. You might as well be firing the shots that are killing your crew if you don't hold them to a high standard and give them the best tools to win the fight. This story illustrates what an advantage a high level of training means when SHTF.

<span>“Wars may be fought with weapons, but they are won by men. It is the spirit of the men who follow and of the man who leads that gains the victory.”</span>

<p><img></img> General George S. Patton quote</p>

'Train Hard, Fight Easy' indeed! The best lessons are those that have been proven right, time and time again, and they surface throughout recorded history.

<p>

</p><p><span><span>'..their drills are bloodless battles, their battles bloody drills.'</span></span>

</p><p><span><span>Flavius Josephus 1st century AD historian on Roman Legion training</span></span>

</p>

will it be ready for the kind of damage short range firefight incurs?

Whenever I jump on the Survivability bandwagon, folks kneejerk to the assumption I am advocating building impervious to all damage, megatonned armored, battlestar galacticas...or somesuch.

But its in the careful design details that Vulnerability Reduction pasy off.

Great example here:

<span> One shell struck amidships, and another punched into the engine room. But the third shell tore through the raider’s funnel, severing the oil warming lines and sending burning fluids cascading down into the motor room to ignite a major fire.</span>

While perfecftly acceptable in a freighter, those vulnerable oil lines in the stack started the "cascading kill chain" which eventually led to the Komoran's loss.

True, she did take other significant damage from further shell fire, but it was that uncontained main space fire that was the most debilitaiting wound for her.

Fast forward to today...And the LCS...take a gander at all the vulnerable systems draped along her interior hull sides, just waiting for debilitating "splinter damage" to put her very quickly into an in extremis status if she were ever unucky enough to find herself in an close in slug out.

So its not armor, so much as its careful thought in the design phases -EARLY- about where and how such systems should be placed that matter most in designing a ship to be "Survivable".

Every bit as important as all the really kewl (and high profit for the Primes) electronic gizmo stuff that everyone usually focuses on.

This blast from a simulated MINE would have immediately done at least a mission kill on any LCS:

http://www.navy.mil/search/photolist.asp

at least NAVSEA made LPD-17 Class grade A shock warships. Too bad they keep destroying their main diesel engines before they ever deploy ! But, hey, it's only 2011, and we're just now beginning to figure out by trial and error how to prevent Lube Oil from getting contaminated and ruining brand new Fairbanks Morse fine diesel engines. Give the Navy a few more years and another couple of LPD's to practice on.

Wish USN could plan on eventually having LCS warships which will also be Mine Countermeasure ships, pass a GRADE A shock requirement. But that would add another $455,000,000 to each LCS.

ok, here's the actual close up photo of the huge Blast next to LPD-19 a couple of years ago.

http://www.navy.mil/management/photodb/photos/080816-N-6031Q-213.jpg

there were a total of 3 blasts and this was the smallest, and farthest away.

Very interesting, it was uncontrollable fires that destroyed HMS Sheffield, and most of carriers lost in the Pacific (Midway!)... certainly warships need to be built differently than commercial vessels, as shown with the Kormoran example.

TIME FOR CELEBRATION!!!!!

AND A NEW FbF!!!!!!!

THEY GOT THE GOAT FORNICATIN' BASTARD!!!!!!!!!

BZ

(puts a new context on the Gates/Panetta/Petraeus shuffle)

NBC just announced a Navy Seal team.

BRAVO FUC|(ING ZULU!!!!!

in the end it took a small team of brave men with small arms...

waiting for the obligatory "ultimate weapon" quote :P

best news since long time!

Post a Comment