Because Ryan demands ... and its a good'un.

Because Ryan demands ... and its a good'un.For the SMS Seydlitz, it is tempting just to say that her story is the story of the Battle of Jutland - but that is too easy. There is a lot more to her story than that - but because it was her finest hour - when I do talk tactical, we'll stick to Jutland.

First though, I want you to think about warship design in the USA since the late '90s, then read the following with a close eye to the timeline.

SMS Seydlitz was a 25,000-metric ton battlecruiser of the Kaiserliche Marine, built in Hamburg, Germany. She was ordered in 1910 and commissioned in May 1913, the fourth battlecruiser built for the High Seas Fleet. She was named after Friedrich Wilhelm von Seydlitz, a Prussian general during the reign of King Frederick the Great and the Seven Years' War.Here are the details of the timeline above.

Seydlitz represented the culmination of the first generation of German battlecruisers, which had started with the Von der Tann in 1906, and continued with the pair of Moltke class battlecruisers ordered in 1907 and 1908. Seydlitz featured several incremental improvements over the preceding designs, including a redesigned propulsion system and an improved armor layout. The ship was also significantly larger than her predecessors—she was approximately 3,000 metric tons heavier than the Moltke class ships.

Despite the success of the previous German battlecruisers designs—those of Von der Tann and the Moltke class—there was still significant debate as to how new ships of the type were to be designed. In 1909, the Reichsmarineamt (Navy Department) requested Admiral Alfred von Tirpitz, the State Secretary, provide them with the improvements that would be necessary for the next battlecruiser design. Tirpitz continued to push for the use of battlecruisers solely as fleet scouts and to destroy enemy cruisers, along the lines of the battlecruisers employed by the British Royal Navy. The Kaiser, Wilhelm II, and the majority of the Navy Department argued that due to Germany's numerical inferiority compared to the Royal Navy, the ships would also have to fight in the line of battle. Ultimately, the Kaiser and the Navy Department won the debate, and the battlecruiser for the 1909–1910 building year would continue in the pattern of the previous Von der Tann and Moltke class designs.Debate based on recent experience with a proven platform ... and resulting action. All in less than half a decade. Yes, to us the technology is simpler - but 100 years ago it was no less "new" than the electric drive and other "new" systems we talk about now.

Remember - the average Navy Commander in 1910 was a Midshipman in the 1880s, if not earlier with the slow promotions of the pre-war period. No, the "you can move faster then" excuse does not hold water for me. These men also did not have computers and the raft of information technology that we have .... perhaps that was an advantage too? No, I don't buy that excuse either.

Shipbuilding pressure from the legislature? New? Snort.

Some of the best things learned for us are from the Seydlitz's CO, Kommandant Kapitän zur See von Egidy's report. As important in 2010 as they were a century ago.

Training and the importance of questioning established procedures.

Shipbuilding pressure from the legislature? New? Snort.

Financial constraints meant that there would have to be a trade-off between speed, battle capabilities, and displacement. The initial design specifications mandated that speed was to have been at least as high as with the Moltke class, and that the ship was to have been armed with either eight 305 mm (12.0 in) guns or ten 280 mm (11.0 in) guns. The design staff considered triple turrets, but these were discarded when it was decided that the standard 280 mm twin turret was sufficient.Enough lessons for now - lets get to the role that defined her; in the thick of it at Jutland.

In August 1909, the Reichstag stated that it would tolerate no increases in cost over the Moltke-class battlecruisers, and so for a time, the Navy Department considered shelving the new design and to instead build a third Moltke class ship. Admiral Tirpitz was able to negotiate a discount on armor plate from both Krupp and Dillingen; Tirpitz also pressured the ship's builder, Blohm and Voss, for a discount. These cost reductions freed up sufficient funds to make some material improvements to the design. On 27 January 1910, the Kaiser approved the design for the new ship, ordered under the provisional name "Cruiser J".

On the night of 30 May 1916, Seydlitz and the other four battlecruisers of the I Scouting Group lay in anchor in the Jade roadstead. The following morning, at 02:00 CET, the ships slowly steamed out towards the Skagerrak at a speed of 16 knots (30 km/h). By this time, Hipper had transferred his flag from Seydlitz to the newer battlecruiser Lützow. Seydlitz took her place in the center of the line, to the rear of Derfflinger and ahead of Moltke The II Scouting Group, consisting of the light cruisers Frankfurt, Rear Admiral Bödicker's flagship, Wiesbaden, Pillau, and Elbing, and 30 torpedo boats of the II, VI, and IX Flotillas, accompanied Hipper's battlecruisers.

An hour and a half later, the High Seas Fleet under the command of Admiral Scheer left the Jade; the force was composed of 16 dreadnoughts. The High Seas Fleet was accompanied by the IV Scouting Group, composed of the light cruisers Stettin, München, Hamburg, Frauenlob, and Stuttgart, and 31 torpedo boats of the I, III, V, and VII Flotillas, led by the light cruiser Rostock. The six pre-dreadnoughts of the II Battle Squadron had departed from the Elbe roads at 02:45, and rendezvoused with the battle fleet at 5:00.

Shortly before 16:00, Hipper's force encountered Vice Admiral Beatty's battlecruiser squadron. The German ships were the first to open fire, at a range of approximately 15,000 yards (14,000 m). The British rangefinders had misread the range to their German targets, and so the first salvos fired by the British ships fell a mile past the German battlecruisers. As the two lines of battlecruisers deployed to engage each other, Seydlitz began to duel with her opposite in the British line, Queen Mary. By 16:54, the range between the ships decreased to 12,900 yards (11,800 m), which enabled Seydlitz's secondary battery to enter the fray. She was close enough to the ships of the British 9th and 10th Destroyer Flotillas that her secondary guns could effectively engage them. The other four German battlecruisers employed their secondary battery against the British battlecruisers.

Between 16:55 and 16:57, Seydlitz was struck by two heavy caliber shells from Queen Mary. The first shell penetrated the side of the ship five feet above the main battery deck, and caused a number of small fires. The second shell penetrated the barbette of the aft superfiring turret. Four propellant charges were ignited in the working chamber; the resulting fire flashed up into the turret and down to the magazine. The anti-flash precautions that had been put in place after the explosion at Dogger Bank prevented any further propellant explosions. Regardless, the turret was destroyed and most of the gun crew had been killed in the blaze.By 17:25, the British battlecruisers were taking a severe battering from their German opponents. Indefatigable had been destroyed by a salvo from Von der Tann approximately 20 minutes before, and Beatty sought to turn his ships away by 2 degrees in order to regroup, while the Queen Elizabeth-class battleships of the 5th Battle Squadron arrived on the scene and provided covering fire. As the British battlecruisers began to turn away, Seydlitz and Derfflinger were able to concentrate their fire on Queen Mary. Witnesses reported at least 5 shells from two salvos hit the ship, which caused an intense explosion that ripped the Queen Mary in half. Shortly after the destruction of Queen Mary, both British and German destroyers attempted to make torpedo attacks on the opposing lines. One British torpedo struck Seydlitz at 17:57. The torpedo hit the ship directly below the fore turret, slightly aft of where she had been mined the month before. The explosion tore a hole 40 feet long by 13 feet wide (12 m × 4.0 m), and caused a slight list. Despite the damage, the ship was still able to maintain her top speed, and kept position in the line.

The leading ships of the German battle fleet had by 18:00 come within effective range of the British ships, and had begun trading shots with the British battlecruisers and Queen Elizabeth-class battleships. Between 18:09 and 18:19, Seydlitz was hit by a 380 mm (15 in) shell from either Barham or Valiant. This shell struck the face of the port wing turret and disabled the guns. A second 380 mm shell penetrated the already disabled aft superfiring turret and detonated the cordite charges that had not already burned. The ship also had two of her 150 mm guns disabled from British gunfire, and the rear turret lost its right-hand gun.

As the evening wore on, visibility steadily decreased for the German ships. Seydlitz's commander, Kapitän zur See von Egidy, later remarked:"Visibility had generally become unfavorable. There was a dense mist, so that as a rule only the flashes of the enemy's guns, but not the ships themselves, could be seen. Our distance had been reduced from 18,000 to 13,000 yards. From north-west to north-east we had before us a hostile line firing its guns, though in the mist we could only glimpse the flashes from time to time. It was a mighty and terrible spectacle."At around 19:00, Beatty's forces were nearing the main body of the Grand Fleet, and to delay the discovery of the Grand Fleet's location by the German fleet, he turned his ships towards the German line, in order to force them to turn as well. This reduced the distance between the British and German battlecruisers from 14,000 to 12,000 yards (13,000 to 11,000 m). Visibility continued to favor the British, and the German battlecruisers paid the price. Over the next several minutes, Seydlitz was hit six times, primarily on the forward section of the ship. A fire started under the ship's forecastle. The smothering fire from Beatty's ships forced Hipper to temporarily withdraw his battlecruisers to the southwest. As the ships withdrew, Seydlitz began taking on more water, and the list to starboard worsened. The ship was thoroughly flooded above the middle deck in the fore compartments, and had nearly lost all buoyancy.

...

The German fleet was instead sailing west, but Scheer ordered a second 16-point turn, which reversed course and pointed his ships at the center of the British fleet. The German fleet came under intense fire from the British line, and Scheer sent Seydlitz, Von der Tann, Moltke, and Derfflinger at high speed towards the British fleet, in an attempt to disrupt their formation and gain time for his main force to retreat. By 20:17, the German battlecruisers had closed to within 7,700 yards (7,000 m) of Colossus, at which point Scheer directed the ships to engage the lead ship of the British line. Seydlitz managed to hit Colossus once, but caused only minor damage to the ship's superstructure. Three minutes later, the German battlecruisers turned in retreat, covered by a torpedo boat attack.

...

A pause in the battle at dusk allowed Seydlitz and the other German battlecruisers to cut away wreckage that interfered with the main guns, extinguish fires, repair the fire control and signal equipment, and ready the searchlights for nighttime action. During this period, the German fleet reorganized into a well-ordered formation in reverse order, when the German light forces encountered the British screen shortly after 21:00. The renewed gunfire gained Beatty's attention, so he turned his battlecruisers westward. At 21:09, he sighted the German battlecruisers, and drew to within 8,500 yards (7,800 m) before opening fire at 20:20. In the ensuing melee, Seydlitz was hit several times; one shell struck the rear gun turret and other hit the ship's bridge. The entire bridge crew was killed and several men in the conning tower were wounded.[

...

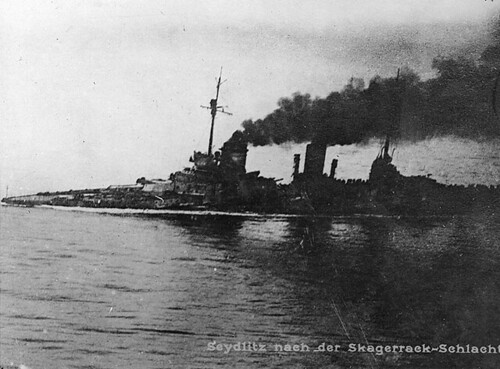

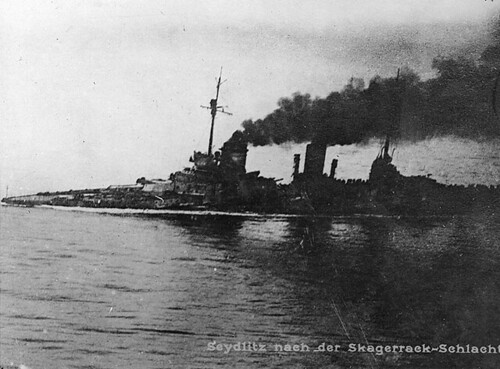

At 00:45, Seydlitz was attempting to thread her way through the British fleet, but was sighted by the dreadnought Agincourt and noted as a "ship or Destroyer". Agincourt's captain did not want to risk giving away his ship's position, and so allowed her to pass. By 01:12, Seydlitz had managed to slip through the British fleet, and she was able to head for the safety of Horns Reef. At approximately 03:40, she scraped over Horns Reef. Both of the ship's gyro-compasses had failed, so the light cruiser Pillau was sent to guide the ship home. By 15:30 on 1 June, Seydlitz was in critical condition; the bow was nearly completely submerged, and the only buoyancy that remained in the forward section of the ship was the broadside torpedo room. Preparations were being made to evacuate the wounded crew when a pair of pump steamers arrived on the scene. The ships were able to stabilize Seydlitz's flooding, and the ship managed to limp back to port. She reached the outer Jade river on the morning of 2 June, and on 3 June the ship entered Entrance III of the Wilhelmshaven Lock. At most, Seydlitz had been flooded by 5,308 tonnes (5,224 long tons) of water.

Some of the best things learned for us are from the Seydlitz's CO, Kommandant Kapitän zur See von Egidy's report. As important in 2010 as they were a century ago.

Training and the importance of questioning established procedures.

The first hit we received was a 12-inch shell that struck Number Six 6-inch casemate on the starboard side, killing everybody except the Padre who, on his way to his battle-station down below, had wanted to take a look at the men and at the British, too. By an odd coincidence we had, at our first battle practice in 1913, assumed the same kind of hit and by the same adversary, the Queen Mary. Splinters perforated air leads in the bunker below and gas consequently entered the starboard main turbine compartment.The importance of inspections - and the love of the hardest ones once you are in harm's way.

Somewhat later the gunnery central station deep down reported: "No answer from 'C' turret. Smoke and gas pouring out of the voice pipes from 'C' turret." That sounded like the time of Dogger Bank. Then it had been "C" and "D" turrets. A shell had burst outside, making only a small hole, but a red-hot piece of steel had ignited a cartridge, the flash setting fire to 13,000 pounds of cordite. 190 men had been killed, and the two turrets had been put out of action. Afterwards, a through examination showed that everything had been done in accordance with regulations. I told the gunnery officer: "If we lose 190 men and almost the whole ship in accordance with regulations then they are somehow wrong." Therefore we made technical improvements and changed our methods of training as well as the regulations. This time only one cartridge caught fire, the flash did not reach the magazines, and so we lost only 20 dead or severely burned, and only one turret was put out of action.

In the conning tower we were kept busy, too. "Steering failure" reported the helmsman and automatically shouted down from the armoured shaft to the control room: "Steer from control room." The order: "Steer from tiller flat" was the last resort. We felt considerable relief when the red helm indicator followed orders. The ship handling officer drew a deep breath: "Exactly as at the admiral's inspection."... and as is my experience as well - the Liberty Risk Sailor is often the Indispensable Warrior.

The helmsman was a splendid seaman but every six months or so he could not help hitting the bottle. Then he felt the urge to stand on his head in the market square of Wihlemshaven. Each time this meant the loss of his Able Seaman's stripe. At Jutland he stood at the helm for 24 hours on end. He got the stripe back and was the only AB in the fleet to receive the Iron Cross 1st Class.The need to stress individual action in response to unforeseen challenges - act without orders if needed - and leaders should let their Sailors know you trust their judgement to act.

The first casualty in the conning tower was a signal yeoman, who collapsed silently after a splinter had pierced his neck. A signalman took over his headphone in addition to his own. In our battle training we had overlooked this possibility.To h3ll with regulation written by those who don't fight.

...

Our aerials were soon in pieces, rendering our ship deaf and dumb until a sub-lieutenant and some radio operators rigged new ones. The anti-torpedo net was torn and threatened to foul the propellers, but the boatswain and his party went over the side to lash it. They did it so well that later, in dock, it proved difficult to untie it again.

According to regulations our paymasters were expected in a battle to take down and certify last wills, but we preferred them to prepare cold food forward and aft, and send their stewards round to battle-stations with masses of sandwiches.Combat leadership. Are your LTJG's ready to do this?

"In 'B' turret, there was a tremendous crash, smoke, dust, and general confusion. At the order "Clear the Turret" the turret crew rushed out, using even the traps for the empty cartridges. Then they fell in behind the turret. Then compressed air from Number 3 boiler room cleared away the smoke and gas, and the turret commander went in again, followed by his men. A shell had hit the front plate and a splinter of armour had killed the right gunlayer. The turret missed no more than two or three salvoes."Finally - damage control.

During the course of the battle, Seydlitz was hit 21 times by heavy-caliber shells, twice by secondary battery shells, and once by a torpedo. The ship suffered a total of 98 of her crew killed and 55 wounded. Seydlitz herself fired 376 main battery shells, but only scored approximately 10 hits.

26 comments:

Fullbore the F!

Okay... stupid question time. How many personnel manned the ship to begin with that it could continue on, doing damage control, fighting, caring for 55 wounded and keep from sinking after losing 95 men? Did they stack them like cordwood somewhere and take them home? The Kapitan doesn't say what it took to keep going despite the sheer number killed and how demoralizing that must have been for the crew. And did the yeoman cross train with the signalman to be able to take over or was that a new concept back then? (Seems to have been an unforeseen thing according to Kapitan's notes.) Was the Padre the ship's chaplain or is that what they referred to the Old Man as?

End of stupid question time. Thanks for your patience.

(Love these insightful FBFs)

Great pick, great story. Thanks. :)

DB,

The Brits (who translated it) call their Chaplains "Padre."

Those Cruisers had ~1,000 people onboard. As for morale - training, training, training, and training. That and the knowledge that if you don't do everything you can, you and the rest of those fighting with you are next.

Unlike the other services when they go into combat - on a warship there is no "rear" or "back area." Your ship and everyone in it is on point with a shared fate.

GREAT story CDR! Great lessons to ponder and act upon. Here's one my father told to me about going into action.

He was a Pharmacist's Mate 1st Class, and had been transferred over to LST-202 prior to the Letye invasion. The ship's doctor and other PM had become casualties, and so my father was the sole medical staff for the ship.

Realizing that if things went bad he could be swamped by casualties he did two things: First, he got permission from the Skipper to train men from each section in basic triage and first aid. Tourniquets, splints, basic stuff.

Second, he requisitoned and got two dozen extra sets of Corpsman's web gear with all the contents, the kind that they carried when they went in with the Marines. These had battle dressings, morphine, sulfa, etc. These he stationed at well-marked, easy to reach areas so that if the ship took a hit to the dispensary, they wouldn't lose all the medical gear. It also allowed for a faster response time for casualties, becuase the kits would be nearby, and with people trained to start things until he could get there, it was more likely casulties could surcice.

It's the same sort of "What happens if......." questions that every Officer, Chief and Petty Officer ought to be thinking on a daily basis.

Thanks again for the post.

<span>21 hits and 21 concussion blasts... wow</span>

Tim, sounds like your family is a long line of thinking out of the box people.

Seydlitz survived the "death ride" of Hippers battle-cruisers, something that no naval strategist believed possible in 1913. Which should remind us what a sturdy ship, damage control, a skilled fighting crew, and good leadership can do.

You're not being transformational enough in your thinking. You just don't understand the future. You should die. :-P

Sorta like the crews of Queen Mary and Indefatigable. "They gave their lives for Transformation".

Each side had battle-cruisers. Jackie Fisher ignored fundamental tenets of building capital warships. Tirpitz did not. Funny how those things work out.

<span style="">Thanks CDR, I knew she’d make a perfect FBF. Trade offs between speed an armor, service outside their anticipated duties, lessons learned or left unknown/unlearned after </span><span style="">Dogger Bank</span><span style="">, the battlecruisers of WWI are a compelling story.<span style="mso-spacerun: yes;"> The fact that she fought in each of the major North Atlantic battles, took severe punishment and survived the war to be scuttled in Scapa Flow, that's a FBF ship.</span></span>

Funny thing is Tirpitz tried to lobby for Fisher approach, but was overruled by the Navy dept., and Kaiser, of all people! Plus, reduced funding from the parliament allowed no room for experimentation...

Note the ability to survive underwater damage. German battlecruisers were repeatedly torpedoed and mined. By comparison, the British superdreadnought Audacious sunk after a single mine hit, Marlborough barely made it back after a torpedo hit at Jutland. Interesting that even in case of the heaviest damage, repair times were measured in weeks, not months.

All this ruggedness was achieved on a much lower GDP.

One point IRT the relative combat superiority of the German BC's: The German navy, because it did not have world-wide resposibilities like the RN, was able to trade reduced coal bunkerage and living quarters for increased combat/damage control and compartmentalization improvements. Consequentially, they were superior ships in a fight, but would have been not as effective for a global navy.

note that (further) evolution of the same designs has created legendary resilience of the Bismarck class...

ewok,

Yep, Imperial Germany could not pour money into "transformational" capital ships that set aside some of the basic axioms of warship construction, and was forced to build "transitional" units that stuck to fundamentals.

Who knew?

Actually, the Bismarck was in many ways too much of a copy and not enough of an evolution of design. It largely failed to incorporate many of the lessons the RN and USN learned about battleship armor and design as a result of post-WWI testing. The Bismarck was poorly designed to deal with aircraft (perhaps less of an issue early in WWII) and its armor distribution was inferior to that of comparable new construction.

I'd suggest that Germany's Navy (and its national leadership) failed the test of proper strategic thinking in both world wars. Tirpitz built a fleet consisting of powerful, well-armed and well-armored ships that was intended for exactly one mission: to slug it out with the RN off Heligoland. When the Brits did not oblige, the German Navy found its strategic value minimal until they started using their subs (fleet in being wasn't enough because what mattered was the impact of the British blockade). And Jutland only confirmed that. Had the Brits maintained contact the night of the May 31 (and there are lots of lessons there), they'd have destroyed the High Seas Fleet at dawn on June 1st, superior German armor and ship balance notwithstanding. In part, that was because the RN simply had lots more ships. German ships were individually very good, but they were not good enough to compensate for both numerical inferiority and a flawed strategic concept. Geography only made those things worse.

The lessons the CDR cites are right on in terms of ship design, leadership and all the tactical stuff. The implications of German strategy are at least as relevant.

Kuantan and Leyte showed no battleship was prepared to survive well executed air attack.

And if you read about the Tirpitz, it took 5 ton bombs dropped from strategic bombers to finish her off. Bismarck itself was quite hard to finish off using gunfire and perhaps was even scuttled by own crew. Revolution did indeed happen, but it was a creation of carrier, not in a design of gun ships.

Ernie Pyle made reference to this. He said in one of his columns that while nothing could compare with the day to day misery of being a infantryman, when the time for dying came, sailors tended to die in larger numbers, and in more horrible ways.

I was under the impression that the BISMARK class was more or less an updated VAN DER TAN battle cruiser, with somewhat hevier armor. I know that each of our fast BBs was kept in the Atlantic Fleet, until the next one was commisioned, as a counter to TIRPITZ, since our BBs were faster than the RN ones, and mounted 16 inchers. I wonder how long a fight between TIRPITZ, and BB-64, the Big Badger Boat would have lasted?

In fact Bismarck was evolution, but of no battlecruiser but late WW 1 superdreadnought class

Bayern, battlecruiser evolution tree continued into Scharnhorst class

US had better radar, so probably that would be deciding factor, though resilience of Tirpitz would mean long slugging match...

ewok40,

You are correct. In layout, protection, armament, and hull form, Bismarck and Tirpitz were up-sized descendants of Bayern, with some modifications. Neither Bayern nor Baden were at Jutland. While slightly slower, these vessels could have given the Queen Elizabeths an even fight. They were well protected, excellent sea boats, and had a main battery rate of fire significantly faster than the QEs.

I'll agree that the Bismarck was a powerful and well-armed ship, and also agree that it had its genesis in WWI German ships like the Bayern class, I stand by my view that it was not state-of-the-art compared with post-WWI Allied navy construction (e.g. South Dakota in our Navy or Nelson and KGV in RN). The fact that the Tirpitz survived so long was a testament to the strength of its anchorage and difficulties in attacking it, not any above-and-beyond attributes of her design. The Allies used 5 ton bombs as a means of efficiently finishing her off, not because lesser weapons would not have worked - in fact an earlier air attack by carrier aircraft severely damaged her.

For compa

German ships were also wider in the beam. I think in part because the Royal Navy suffered from restrictions in the size of docks, in part because German ships had to have less draft because of the need to traverse the Kiel Canal between the Baltic and North Sea. Beamier ships, more compartmentalization.

<span>Anthony,

I would maintain that Bismarck and Tirpitz were comparable to both the South Dakotas and the KGVs. Probably slightly more powerful than the North Carolinas. They were faster than all three Allied classes.</span>

Post a Comment