Before diving into today’s post, as we have reached a lot of new readers in the last year, I would beg the indulgence of long-term members of The Front Porch to allow me to review some long-standing positions of mine.

On the foreign policy front, especially for the last decade, I have liked to consider myself a realist. I do not expect perfection in my personal friends, nor expect perfection in my nation’s friends. I am not an isolationist by any stretch, but I do find myself much closer to John Quincy Adams’s;

…admonition that “Americans should not go abroad to slay dragons they do not understand in the name of democracy.”

…than I am to that mindset that brought us to that now clearly disastrous invasion of Iraq in 2003 etc.

For firm realists, I am probably seen as a bit wobbly, but that’s OK as it is fair. I am, for a lack of a better description, a situational realist. For even longer than the 18 years I have put my thoughts down here, I continue to advocate for a complete restructuring of our imperial presence around the world, especially when it comes to our ground forces. All of our friends and allies can more that support significant ground forces to defend their lands. We are a maritime and aerospace power on the other side of the world. We can maintain combined logistics and training facilities with them, and even rotate forces in and out when desired, but we should not be garrisoning their nations with tens of thousands of ground forces as we approach the middle of the 21st Century.

I’m not dogmatic on the topic. I am open to the argument for some forces in South Korea – very few – because integration timelines are so short for that still unresolved war. Other locations, even in Europe, I am much more skeptical about. Even with recent Russian aggression, our allies in Europe should, if we can break their addiction to Uncle Sam’s umbrella, more than handle that threat until, if needed, we need to bring forces across the Atlantic.

I also depart realist dogma when it comes to Ukraine. As the record shows, I have been a regular supporter of helping Ukraine defend herself over the last decade. Russia is, and remains, a bully with an imperial mindset. She started this war, and it is in our interest that she is defeated as her present leadership clearly stated that this was the first of many wars of conquest. Best to stop the Russian neo-imperial effort with Ukrainians on the Dnieper than with Americans on the Oder.

America has a long record of helping those trying to secure self-determination. An imperfect record, but in line with our nation’s founding. We are not, however, to force our beliefs on others. Set and example for others to follow if they so wish, but not force.

That’s the outline, and with that, today I’d like to point you to an article by someone who I disagree with now and then – which is normal and healthy.

You must read widely, and not just the people who think just like you. You need to challenge your ideas with well meaning people of good intention that see solutions to problems differently than you do in whole or in part. No one has a perfect picture, but some are mostly right and others history shows are mostly wrong regardless of their pedigree or alignment with the constellation of your priors. You may dismiss their ideas for lacking merit, find some challenges in them that refines and improves your own, or you might even be provided some insight which leads you to change your own. Normal and healthy.

I’m not aligned with her fully here, but if you want to hear – and you should – what a principled realist argument is, our friend Emma Ashford has a read worth your time over at Foreign Affairs. It is actually a review of the recent books, Matthew Specter’s The Atlantic Realists and Jonathan Kirshner’s An Unwritten Future, but in practice it is much more.

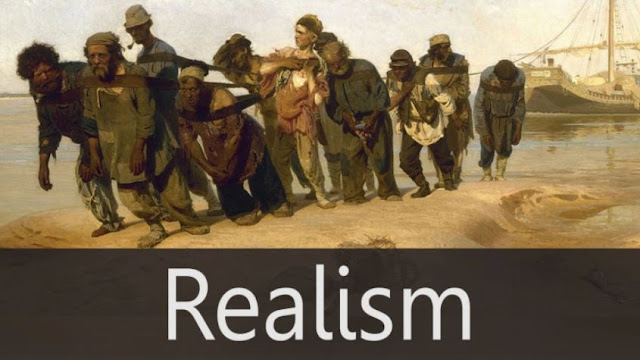

First, let's allow Emma to define "realism" in this context;

What today is called “realism”—the school of thought most undergraduates are taught in their International Relations 101 class—is in fact structural realism or neorealism, a version of realism outlined in the 1970s by the scholar Kenneth Waltz. Neorealism is further divided into “defensive” and “offensive” variants, depending on whether one believes that states primarily seek security through defensive means, such as military fortifications and technology, or through an expansion that acquires power and territory. Both versions focus heavily on structural factors (the ways that states interact at the global level) and effectively ignore domestic politics, the quirks of bureaucratic decision-making, the psychology of leaders, global norms, and international institutions. Neorealism thus stands in stark contrast to the older school of classical realism, which counts Thucydides, Machiavelli, and Bismarck among its earliest practitioners, has strong roots in philosophy, and includes factors such as domestic politics and the role of human nature, prestige, and honor. It also contrasts with classical realism’s more modern counterpart, “neoclassical realism” (a term coined by Gideon Rose, a former editor of this magazine), which seeks to marry the two variants by reincorporating domestic and ideational factors into structural theories.

Now let's dive in to a few pull quotes that hopefully lead you to read the whole thing.

None of these notions are pleasant or popular. The realist Robert Gilpin once titled an article “No One Loves a Political Realist.” All too often, pointing out the harsh realities of international life or noting that states often act in barbaric ways is seen as an endorsement of selfish behavior rather than a simple diagnosis. As one of the school’s founding fathers, Hans Morgenthau, put it, realists may see themselves as simply refusing to “identify the moral aspirations of a particular nation with the moral laws that govern the universe.” But their critics often accuse them of having no morals at all, as the debate over Ukraine has shown.

That is something I find attractive about the realist argument. It accepts the reality of fallen man, our own limitations, and the need for the attenuation of emotion. At its core is humility - a rare but valuable commodity in our age.

Ukraine has long been a flash point for realist thought. Many realists argue that in the post–Cold War period, the United States has been too focused on an idealistic conception of European politics and too blasé about classic geopolitical concerns, such as the enduring meaning of borders and the military balance between Russia and its rivals. Policymakers who subscribed to liberal internationalism—the idea that trade, international institutions, or liberal norms can help build a world where power politics matter less—typically presented NATO’s expansion as a matter of democratic choice for smaller central and eastern European states. Realists, in contrast, argued that it would present a legitimate security concern for Moscow; no matter how benevolent NATO might seem from the West’s perspective, they would argue, no state would be happy with an opposing military alliance moving even closer to its borders.

This argument aligns closely with one of my critiques that is mostly OBE but should be understood; our Ukraine policy was in no small measure run by people who could not see the situation from the Russian perspective. They were Russian experts who had a spreadsheet understanding of Russia, but not a cultural or historical perspective. That ignorance was fortified with an unalloyed belief in their own expertise. They/we were like a stumbling child - meaning no harm but unable to not damage things they/we don't understand.

Yet even if realism is largely present in today’s policy debates as a foil, pushing U.S. foreign policymakers to justify their choices and perhaps adopt slightly more pragmatic options, that may be the best that realists can hope for. As Specter points out, realists have had a complicated relationship with policymaking. Kennan, who served as the U.S. State Department’s director of policy planning, and Morgenthau, who worked under him, are among the best-known realist policymakers, and their influence has waxed and waned over time. The most realist administrations—those of Presidents Richard Nixon and George H. W. Bush—had some notable policy triumphs: ending the Vietnam War, managing the peaceful breakup of the Soviet Union, winning the Gulf War. But they also had mixed legacies, from Nixon’s troubled domestic political record to Bush’s 1992 electoral loss. That is still more than one can say for realist influence in the Clinton, George W. Bush, and Obama administrations, when unchallenged U.S. power allowed idealists to drive most policy. Yet as the world continues its shift toward multipolarity, realist insights will once again become more important for the conduct of U.S. foreign policy.

Perhaps realism at mid-century will have a better seat at the table. Perhaps.

Again, I encourage you to read it all, but in your busy life if you can't, I will leave you as Emma leaves her review. This is the core, and apologies to Hillel, all else is commentary;

Realists accept that foreign policy is often a choice between the lesser of evils. Pretending otherwise—pretending that moral principles or values can override all constraints of power and interest—is not political realism. It is political fantasy.

Photo credit ELACLARRISASIMAMORA.