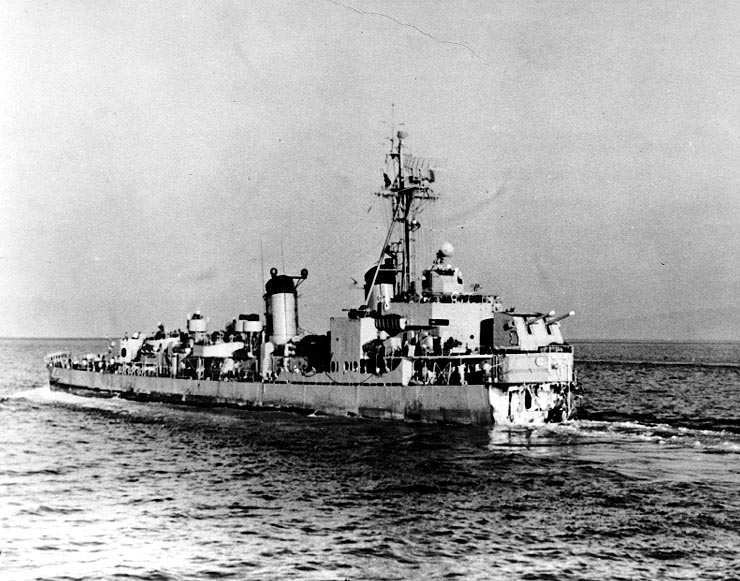

A different FbF today with another example that little to nothing that we do now is "new" or "transformational." The central core remains the same. To win you need a Joint effort of land and sea forces working under a common, well understood Strategic and Operational framework - led and executed by well trained, audacious and visionary (and often flawed) leaders. It has been around for thousands of years.

A different FbF today with another example that little to nothing that we do now is "new" or "transformational." The central core remains the same. To win you need a Joint effort of land and sea forces working under a common, well understood Strategic and Operational framework - led and executed by well trained, audacious and visionary (and often flawed) leaders. It has been around for thousands of years.

Most have seen 300, and know about Battle of Thermopylae and Leonidas - but how many of you know about a great master of the Joint battlespace Themistocles - and his masterpiece of the Battle of Artemisium?

Often overshadowed by the more famous Salamis, it was won by the same Themistocles, one of those critical men who was at the right place at the right time. Seeing the future threat of the Persians following the Battle of Marathon where he fought - by hook and by crook he saw that he would pursue success in securing the key to the freedom of the Greek city-states, and the weakness of an invading Persian army. Over 2,000 years before a Prussian General started legions of arm-chair strategists - Themistocles knew Center of Gravity.

He knew that a large land army couldn't supply itself without a mastery of the sea. Either on the Tactical, Operational, or Strategic level - the Persians could not succeed if they did not master and control the sea.

The Greeks could not face and be victorious over the Persians by land armies alone. He knew that.

Thing is; he as almost alone. Through a combination of politics, guile, force of personality, and a fib or two, he managed to build a fleet that showed up just in time. Just in time to fight the sea battle that occurred at the same time as the Spartan and Tespian stand at Thermopylae.

While they held on land, he bloodies the Persian's nose at sea. You should read all of Herodotus Book 8 to see the sides of man that never changes, but here is the juicy bits. At what modern historians say was a Greek fleet outnumbered 6 or 8 to 1.[8.10] When the Persian commanders and crews saw the Greeks thus boldly sailing towards them with their few ships, they thought them possessed with madness, and went out to meet them, expecting (as indeed seemed likely enough) that they would take all their vessels with the greatest ease. The Greek ships were so few, and their own so far outnumbered them, and sailed so much better, that they resolved, seeing their advantage, to encompass their foe on every side. And now such of the Ionians as wished well to the Grecian cause and served in the Persian fleet unwillingly, seeing their countrymen surrounded, were sorely distressed; for they felt sure that not one of them would ever make his escape, so poor an opinion had they of the strength of the Greeks. On the other hand, such as saw with pleasure the attack on Greece, now vied eagerly with each other which should be the first to make prize of an Athenian ship, and thereby to secure himself a rich reward from the king. For through both the hosts none were so much accounted of as the Athenians.

[8.11] The Greeks, at a signal, brought the sterns of their ships together into a small compass, and turned their prows on every side towards the barbarians; after which, at a second signal, although inclosed within a narrow space, and closely pressed upon by the foe, yet they fell bravely to work, and captured thirty ships of the barbarians, at the same time taking prisoner Philaon, the son of Chersis, and brother of Gorgus king of Salamis, a man of much repute in the fleet. The first who made prize of a ship of the enemy was Lycomedes the son of Aeschreas, an Athenian, who was afterwards adjudged the meed of valour. Victory however was still doubtful when night came on, and put a stop to the combat. The Greeks sailed back to Artemisium; and the barbarians returned to Aphetae, much surprised at the result, which was far other than they had looked for. In this battle only one of the Greeks who fought on the side of the king deserted and joined his countrymen. This was Antidorus of Lemnos, whom the Athenians rewarded for his desertion by the present of a piece of land in Salamis.

The layers to this is great in so many ways. You see, you can read from Plutarch himself here. There are weak-willed politicians, jealousy and pettyness among Flag Officers, competing ideas on how to win and why. Unreliable allies, vanity, courage, cowardice and shame. And at the center of it all - a man who know what needed to be done.Having taken upon himself the command of the Athenian forces, he immediately endeavoured to persuade the citizens to leave the city, and to embark upon their galleys, and meet with the Persians at a great distance from Greece; but many being against this, he led a large force, together with the Lacedaemonians, into Tempe, that in this pass they might maintain the safety of Thessaly, which had not as yet declared for the king; but when they returned without performing anything, and it was known that not only the Thessalians, but all as far as Boeotia, was going over to Xerxes, then the Athenians more willingly hearkened to the advice of Themistocles to fight by sea, and sent him with a fleet to guard the straits of Artemisium.

When the contingents met here, the Greeks would have the Lacedaemonians to command, and Eurybiades to be their admiral; but the Athenians, who surpassed all the rest together in number of vessels, would not submit to come after any other, till Themistocles, perceiving the danger of the contest, yielded his own command to Eurybiades, and got the Athenians to submit, extenuating the loss by persuading them, that if in this war they behaved themselves like men, he would answer for it after that, that the Greeks, of their own will, would submit to their command. And by this moderation of his, it is evident that he was the chief means of the deliverance of Greece, and gained the Athenians the glory of alike surpassing their enemies in valour, and their confederates in wisdom.

When the contingents met here, the Greeks would have the Lacedaemonians to command, and Eurybiades to be their admiral; but the Athenians, who surpassed all the rest together in number of vessels, would not submit to come after any other, till Themistocles, perceiving the danger of the contest, yielded his own command to Eurybiades, and got the Athenians to submit, extenuating the loss by persuading them, that if in this war they behaved themselves like men, he would answer for it after that, that the Greeks, of their own will, would submit to their command. And by this moderation of his, it is evident that he was the chief means of the deliverance of Greece, and gained the Athenians the glory of alike surpassing their enemies in valour, and their confederates in wisdom.

As soon as the Persian armada arrived at Aphetae, Eurybiades was astonished to see such a vast number of vessels before him, and being informed that two hundred more were sailing around behind the island of Sciathus, he immediately determined to retire farther into Greece, and to sail back into some part of Peloponnesus, where their land army and their fleet might join, for he looked upon the Persian forces to be altogether unassailable by sea. But the Euboeans, fearing that the Greeks would forsake them, and leave them to the mercy of the enemy, sent Pelagon to confer privately with Themistocles, taking with him a good sum of money, which, as Herodotus reports, he accepted and gave to Eurybiades. In this affair none of his own countrymen opposed him so much as Architeles, captain of the sacred galley, who, having no money to supply his seamen, was eager to go home; but Themistocles so incensed the Athenians against them, that they set upon him and left him not so much as his supper, at which Architeles was much surprised, and took it very ill; but Themistocles immediately sent him in a chest a service of provisions, and at the bottom of it a talent of silver, desiring him to sup tonight, and to-morrow provide for his seamen; if not, he would report it among the Athenians that he had received money from the enemy. So Phanias the Lesbian tells the story.

Though the fights between the Greeks and Persians in the straits of Euboea were not so important as to make any final decision of the war, yet the experience which the Greeks obtained in them was of great advantage; for thus, by actual trial and in real danger, they found out that neither number of ships, nor riches and ornaments, nor boasting shouts, nor barbarous songs of victory, were any way terrible to men that knew how to fight, and were resolved to come hand to hand with their enemies; these things they were to despise, and to come up close and grapple with their foes. This Pindar appears to have seen, and says justly enough of the fight at Artemisium, that-

"There the sons of Athens set The stone that freedom stands on yet."

More modern commentary here, here, here, and here.