Following is an address delivered by Claude Berube, PhD in which he was asked to address the issue of readiness for war at the Annual Congress of the Naval Order of the United States. I asked him to make it available here.

Claude, over to you!

Thank you, John, for your kind introduction and to my fellow companions of the Naval Order of the United States for having invited me to speak at this annual congress. The views I express today are my own and not those of the Navy or any other organization with which I am affiliated.

When John Shanahan and others invited to address you, they asked me to talk about the navy of yesterday and of today with regard to readiness and discuss themes in some of my recent articles. To be frank, I was stumped. How do you condense our two centuries of history and apply it to today in about 30 minutes? In the end, I realized that I needed to frame this as a former hockey player because where I grew up, there were two houses of worship – the Catholic churches and the hockey rinks.

You see, I had this hockey coach. In the early pre-dawn practices, he’d yell at us to skate faster, hit harder, and pass more accurately. He’d yell at us when we didn’t pass to the right person during a game. He’d yell at me because I was sent to the penalty box - again. He didn’t yell because he didn’t like us. He loved the team. He was there for us. He wanted to improve our game. He wanted us to win. I want the Navy to win. And so, in that vein, ladies and gentlemen, I hope you will allow me to share a few thoughts on the question of readiness yesterday and today out of love – but without the yelling…

Our robust navy is comprised of aviation, submarine, cyber, supply, and other elements, and I fully recognize that any evaluation is incomplete without a quantifiable or qualitative assessment of those elements and their capabilities. Nevertheless, I would like to simply focus on one element – the surface navy – because it provides a unique historical thread. And in the interest of the limits of our time today I appreciate your understanding why I am truncating this to its most basic elements.

I would argue we’ve never been truly ready for war or other operations. We have done the job with what we have and what we would quickly build or assemble. To paraphrase a former secretary of defense, you go to war with the navy you have, not the navy you want.

The need for a navy has been recognized for thousands of years. The Athenian Themistocles said that “he who controls the sea controls everything.” And you cannot control the sea without a sufficient navy. By the American Revolution, we had our own naval advocate in John Paul Jones who said, “in time of peace, it is necessary to prepare, and always be prepared for war by sea…without a respectable navy, alas America.” But how do you do that?

We can go start at the American Revolution when an ad hoc navy was both constructed and procured, when merchant ships became privateers or, like the Bonhomme Richard converted to a warship. We had a continental navy, state navies, privateers, and an ally with the French navy, but coordination was always a challenge. Harassing British seaborne commerce largely fell to the privateers. During the war, 1,700 letters of marque were issued. In the last year of the war alone there were 450 privateers patrolling the Atlantic seeking British merchant ships as prizes. Privateers captured three times as many prizes as the Continental Navy. British shipping insurance, as a result, increased ten-fold to thirty percent of their cargo value. That made merchants take notice who shared their displeasure with their members of Parliament.

Following the war, absent a navy, the young nation faced a new debate about a new Constitution. And in that debate between the Federalists and Anti-Federalists, we find them just as passionate on whether to have a standing navy and the size of the navy as on any other subject. It is Alexander Hamilton in Federalist Paper 11 who argued for a standing navy – a navy of respectable weight including great ships of the line against maritime powers to place a check on them. In Federalist Paper 41, James Madison argued that the Atlantic states and towns would benefit from naval protection, “if they have hitherto been suffered to sleep quietly in their beds.”

And, so, was born a clause in Article 1 Section 8 of the new United States Constitution that Congress must “provide and maintain a navy.” What remained to be determined, however, is what size to make an eventual navy.

In the subsequent Quasi-War against France, we had our first frigates, but we needed more. Along came the subscription ships that were privately funded – the Essex, the Philadelphia, the George Washington, the Boston, and many others. So too were those privateers, also authorized under the Constitution. The Quasi-War showed the value of a navy and that our frigates could challenge equivalent European ships, but it was supplemented by the private sector.

At the beginning of the War of 1812 the Navy only had some 17 ships. Secretary of the Treasury Albert Gallatin argued America lay up the fleet in New York rather than risk them to the Royal Navy. There were no ships of the line even though naval officers a year before the war argued for a massive building program. Letters of marque were again issued to American privateers which captured approximately 1,200 British prizes.

At the beginning of the Civil War, Secretary of the Navy Gideon Welles inherited a fleet of less than 100 ships, many of which were in disrepair or obsolete. By war’s end the US Navy had more than 600 ships, more than two-thirds of which had been merchant ships converted to wartime operations.

The U.S. had three years to prepare before joining the first world war and when it did, it did so overwhelmingly with its merchant ships, its latest warships, and the ability to transport one million soldiers and Marines without a single loss.

In 1941 the US Navy had 225 surface warships. By war’s end - only 1,370 days later - the arsenal of democracy had built another 600. On December 7, 1941, the navy had a fleet size of 790 ships. By the end of the war, we had a fleet size of 6,768.

We built 2,700 Liberty ships at 18 shipyards, we built 66 Gleaves-class destroyers at 8 shipyards, and 175 Fletcher-class destroyers at 11 shipyards. We build nearly one hundred aircraft carriers and escort carriers. The US lost more than 1,500 merchant ships during the war, but by war’s end had 4,500 ships.

What do these and other conflicts suggest? No, we were not ready in the number of ships we would need for each conflict. However, the United States had a robust merchant service from which to draw ships and sailors, it had shipyards to quickly build or repair ships if needed, and it had time to recover and respond to the initial phases of military operations. It drew heavily from a private sector industrial base.

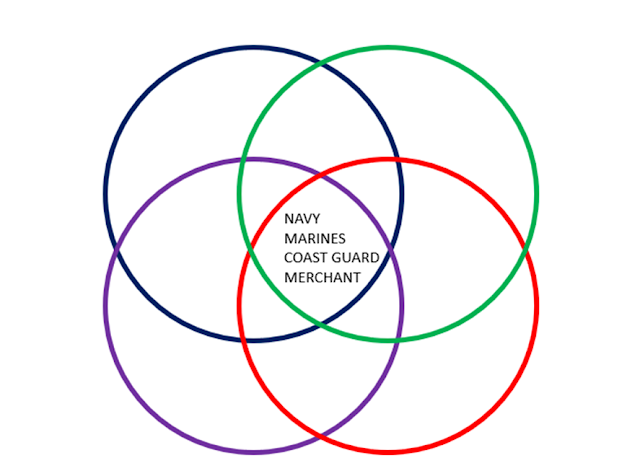

To our second question. Are we ready now? We do have a tremendously capable Navy, Marine Corps, Coast Guard, and Merchant Marine. When we are at sea, we patrol, conduct humanitarian relief missions, etc. But are we ready? No, we are not ready materially or in the numbers needed to challenge the world’s largest navy in their backyard – that is China’s.

The navy has suffered from the diversion of attention and resources to two lengthy-land wars. It has suffered from costly unforced errors in lives, ships and cost. Gone is a major $750 million ship like the Bonhomme Richard in whose strike group I deployed 17 years ago. Hundreds of millions in overhaul investment in the USS Miami, a submarine lost in a fire at the Portsmouth Naval Shipyard. Hundreds of millions and two years in the shipyard for the USS Fitzgerald and USS McCain. A mine warfighting ship lost on a reef. We have lost ships before in our history due to accidents and storms, but we don’t have ships to spare now. We need everything.

We have had three major shipbuilding programs in the past twenty years that have been a challenge. Littoral Combat Ships decommissioning in just a few years. And while Zumwalt and Ford have finally deployed, the time from their commissioning to their first deployments is well beyond the length of US participation in the Second World War. The atomic bomb project went from program establishment to bombs on target in 1,376 days.

Defense news recently reported that the us navy has “spent more than four years repairing one of its amphibious ships, already spending more than $100 million above what was planned. The ship is still not ready to deploy.” The Navy, after $300 million just wants to decommission it. “Only 45% of the amphibious ship fleet is ready today compared to the navy’s 80 percent goal.”

Has the US Navy had programs that didn’t go according to plan? Of course. Although Robert Fulton built the first steam powered warship in 1815, it would be more than two decades when the technology was reliable enough from the private sector to build dual-powered ships. In 1835, Congress debated naval funding and whether to build the 120-gun ship of the line USS Pennsylvania with 1,000 sailors (that was ten percent of the size of the navy in one ship) or a dozen small sloops. In the end, Pennsylvania was built largely because the congressman who represented the shipyard in Philadelphia where it was to be built was Chair of the Naval Affairs Committee. There was the ram ship USS Katahdin, commissioned in 1896 and decommissioned only a year later.

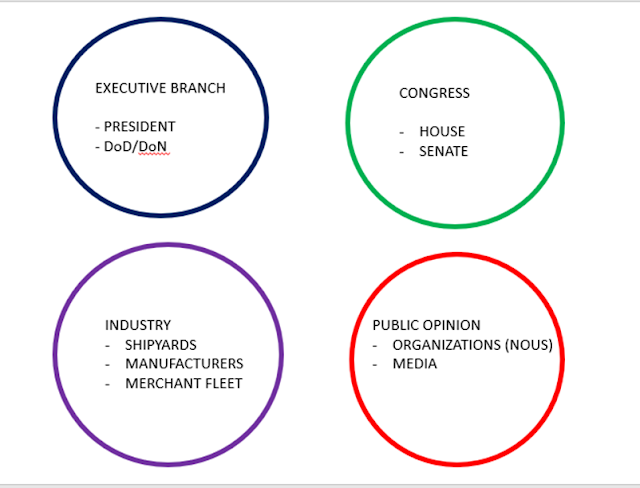

To be ready and sufficiently sized is based on four elements: the executive branch, Congress, industry, and public support.

All those elements feed into each other. When all come together, that’s when we see a rejuvenation of the maritime services. Diminish or remove any one of those out and the equation falls apart.

At every period we increased the size and platform diversity, we had an executive branch that provided the vision and support. Even Andrew Jackson whom I wrote about in my latest book, had a recognizable maritime strategy. Others like the two Adams’, the two Roosevelts, Wilson, and Reagan understood the role of a navy and were its supporters.

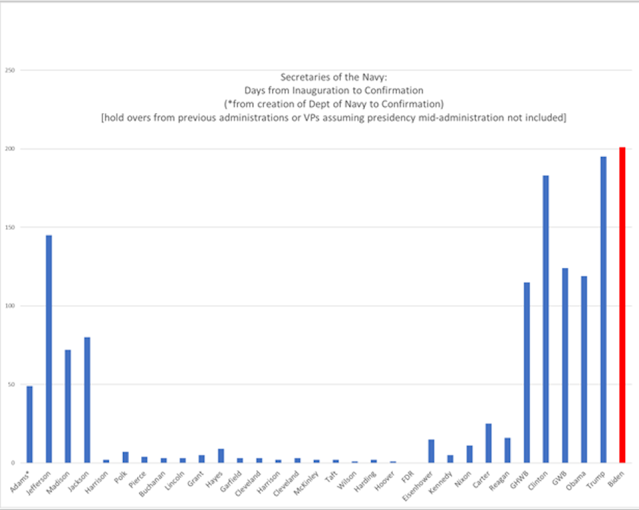

How do you quantify administration interest in the Navy? We can start with a simple criterion. Under the current administration, it took more than 200 days for a Secretary of the Navy to be confirmed – that’s a longer period from inauguration to confirmation than any other presidency.

Second, every period has had a critical mass of supporters from the legislative branch which has the Constitutional authority and responsibility to provide and maintain a navy. Absent that critical mass of support, a Navy will not be built or built better.

While watching a House Armed Services Committee hearing this year, I was struck by how a member of congress advocating for the navy was interrupted by the Chairman with this statement about China’s navy.

“How capable are their ships? How many ships does China have deployed all around the world in any given moment? That’s a very low number from what I understand. And the capability of those ships are not as great either. So, we can all like FREAK ourselves out about all the trillions of dollars a year apparently, we have to spend on our defense budget. I think it would be helpful if we had a realistic understanding of our adversaries and where they’re at.”

He dismissed the threat of China, and he dismissed the idea of building the navy up.

I certainly respect the chairman and his role, but fundamentally disagree with his off-the-cuff assessment. China may have a low deployment rate focusing only on two regions, but it is not dissimilar to the US Navy’s rate of 15 percent in the 1980s especially when you consider it isn’t committing itself – yet – to all the regions of the world. We could do so because we had the numbers. Today our deployment rate is about 35 percent. The pace of China’s shipbuilding has meant that their ships have rarely needed to deploy more than a couple of times. Its growing fleet has allowed China to do more without degrading the material readiness of the ships. Conversely, the has struggled to maintain its ships, which are deploying at a higher rate and for longer periods.

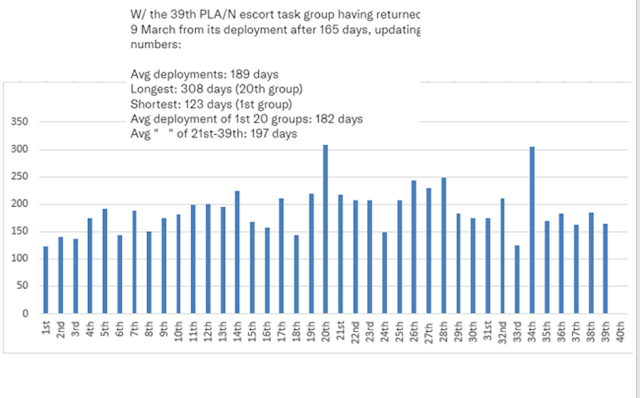

Capability comes from both technology and experience and China’s navy is gaining experience very quickly. In the past decade they’ve been sending squadrons – 42 of them -to the Horn of Africa every three or four months.They have gained experience close to their shores and ships from every one of their fleets is operating on the other side of the world in deploying to the Horn of Africa.They have vastly outbuilt us in the past 10 years. Yes, that red line is China’s shipbuilding versus the blue of the us navy.

This graph represents all the major surface combatants in our fleet as of last year and their age from commissioning, so the top are the oldest ships in each fleet and the newest at the bottom. Eighty – that’s eight zero – of their surface fleet has been built in the past decade. By contrast only twenty percent of the US fleet is less than a decade old.

Testifying before the Senate Armed Services Committee in June, the Secretary of Defense said we “certainly have the most capable and dominant navy in the world and it will continue to be so going forward.” While the secretary’s sentiment is laudable, it is contrary to quantifiable trends. China isn’t a rising power – it has risen. I think we need to consider another historical example when we casually brush aside the threat of China’s navy.

Commodore Matthew Perry visited Japan in 1854. That caused Japan to think about a navy of its own, not dissimilar to how China reacted 1996 to the Nimitz battle group transiting the Taiwan strait. In 1874, Japan launched an expedition to Taiwan. That decade their midshipmen began to study at the US Naval Academy. By 1895 their navy defeated China’s fleet in a war. In 1905, they defeated the entire Russian Eastern and Baltic fleets.

For those reasons, I think the chairman’s remarks were either insufficiently informed or intentionally dismissive.

We have incredible advocates in Congress like Elaine Luria [note: this speech was delivered before the 2022 election] and Mike Gallagher. But we need a legislative branch with advocates beyond that and beyond the shipbuilding districts. We are mired in petty partisan politics while China has a distinct advantage – they are forcibly unified and that has enabled them to build the world’s largest fleet. While we need to defend our democratic republic ideals, we need to find a way to unify.

The third element - in nearly every one of our previous conflicts, we relied heavily on the capacity of our industrial base especially shipyards. How many do we have today? To give you the scope of what we face, one shipyard in China has more capacity than all of our shipyards combined. Our shipyard capacity is limited. A 2021 Congressional Budget Office report pointed out that the four submarine shipyards were facing significant delays in completing maintenance because of the amount of work necessary has increased and they are having trouble finding workers. This has affected operational readiness.

Part of that industrial base is the size of the us merchant fleet because it was America’s maritime economy…. China has some 4,500 merchant ships; there are fewer than 80 in the US fleet. Why is this important? Because the maritime economy that built the nation in the 19th century meant shipyard jobs. It meant jobs across the nation which built systems on those ships. It meant that many families had someone who relied on the sea for it or on it. And that merchant fleet needed protection by the US Navy. That is why the public could understand the need for a navy – because it was self-interested in it. Self-interest and passion drives politics and public policy, not reason and data. But the American public has become estranged from the maritime economy that would have been familiar to our forebears.

Earlier, I mentioned several wars but I saved one for the end. That is the war that really put the United States Navy on a global footing because it demonstrated the power of our industrial base, our ability to build modern ships, the vision of presidents, the support of congress, and an emotional support from the media and general public. That, of course, is the Spanish-American war. It is why I think it a particularly relevant war to discuss today because less than a decade before, the naval order of the United States was established by people who recognized we had a problem, who had a vision, and made the vision of a navy a reality.

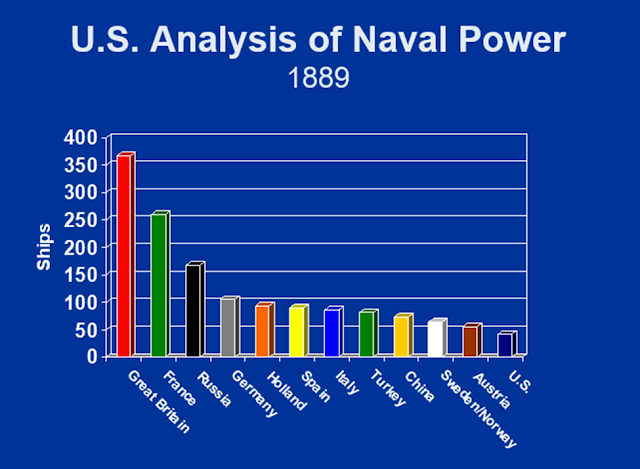

The year before the Naval Order was established, the US Navy was not among the world powers.

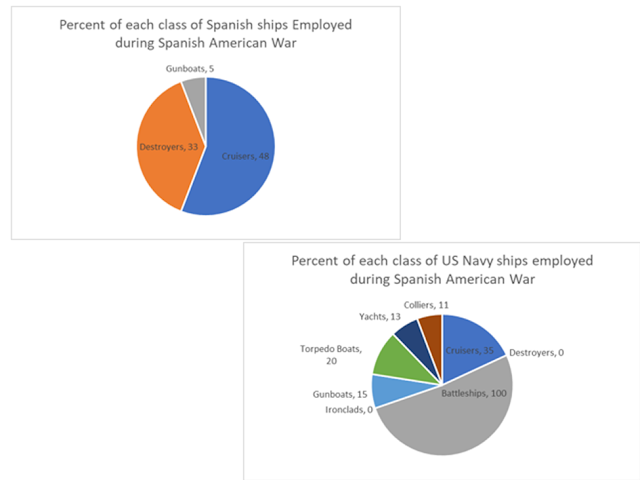

The Spanish navy during the 1890s was a traditional power investing in traditional surface combatants. The young American navy was more diverse in its platforms, understanding the need for logistics ships, etc.The Spanish Minister of Marine, Segismundo Bermejo had assessed the situation like this: the Spanish navy was experienced and a global power; the US Navy was young and inexperienced. On February 15, 1898 – the day the Maine exploded - he wrote to Admiral Cervera that it was his intent to blockade the American coast. The day after Cervera wrote back that the ships of the Havana station were badly worn out and that the Spanish naval force compared to the United States was approximately one to three, therefore a blockade wasn’t possible.

On April 22, three days after the declaration of war, Cervera wrote to Bermejo that “nothing can be expected of this expedition except the total destruction of the fleet or its hasty and demoralized return.” The Colon didn’t have its big guns. The 5.5 inch ammunition, with the exception of about 300 rounds, was bad. Two other ships had defective guns. They didn’t have a single torpedo. The Vizcaya could no longer steam. There was no plan, which he had much desired and suggested in vain. In short, he wrote, “it is a disaster already, and it is to be feared that it will be a more frightful one before long.” Privately, Cervera had been critical of the state of the Spanish navy before this because of its lack of money and frantically inefficient bureaucracy.”

Regardless, Cervera did his duty and in July would face the American fleet off Santiago. In his last address to his squadron, Cervera said “the solemn moment of fighting has come. The sacred name of Spain and the glorious honor of her flag so demands…the enemy covets our old and glorious hulls. They have sent the whole power of their young navy against us so as to achieve this goal. Hoist the flag and surrender no ship. Sound the trumpet for the combat. May God receive our souls.”

Every ship under his command was lost to the Americans. He and 39 of his officers were then held as prisoners of war at the US Naval Academy and treated as heroes by the American public.

What of Spain’s Asiatic fleet that was defeated at Manila Bay? Admiral George Dewey would write in his autobiography, “the Spanish government attempted to make a scape-goat of poor Admiral Montojo, the victim of their own shortcomings and maladministration.”

We would hope to rely on our allies in war and access to distant waters, but I think there’s another lesson from the Spanish-American war, a concern Admiral Dewey wrote about himself in his autobiography. His biggest concern after his victory at Manila Bay was that he’d face more Spanish. Specifically, a third squadron – a relief squadron – had gotten underway from Spain under Admiral Camara. He expected to resupply in Egypt. If Camara had that coal, Dewey wrote, there would be nothing that stopped him. But the coal was denied and Camara was forced to return to Spain. This isn’t unusual. Think about the start of the Iraq war when an entire infantry division was denied access through Turkey. Can we always rely on other nations great and small especially in a potential conflict with China when nations must act in their self-interest?

A final point. Some may argue that China’s navy is only slightly larger than ours. But if war comes and it is anywhere near the South China Sea they will be able to bring to bear their entire fleet in a matter of days – by the end of the decade, the Congressional Research Service estimates they will have 425 ships.

How many of our ships could we get in theater in days or weeks? 100? 150? That would be a one to three advantage, the same concern Cervera voiced about his proportion to the Americans. We have an incredibly capable force and equally impressive sailors. But we have to assess how unique, innovative technology in small numbers will do against a larger force. When I was a defense contractor in the 1990s, one of my senior colleagues was Bud Rundell, a B-17 bomber pilot shot down over Merzberg on his 13th mission. He told me of seeing a Me-262 during one mission, but there were too many bombers to counter that one innovative jet. What of German advances in tanks, submarines, or V-1 and V-2 rockets during the Second World War? How much did unique, advanced technology impact the result against an overwhelming Soviet and Allied force?

To close out, I mentioned at the beginning of my talk that my town had two houses of worship – the hockey arenas and the Catholic churches.

Fifteen years ago, I was in Ottawa sitting in a chapel - the Rideau Street Chapel. Coincidentally it belonged to the same religious order that founded a hospital in my town and where my family worked. As I sat in a pew, I observed the artistry of the fan-vaulted ceilings and listened to a chorus of forty voices. But the chapel was no longer on Rideau Street. It had been deconstructed and moved to the interior of the National Gallery of Canada where speakers played a recording of the chorus. That morning I read in the paper an article about communion hosts – the center piece of the Catholic mass – had found a resurgent popularity in Quebec as a common, secular snack. Unlike my childhood, the churches in Quebec that had a Catholic faith for three centuries was in steep decline, its churches empty, and its foundations were now viewed as artifacts.

A similar feeling struck me a few years ago when I was in England visiting the Portsmouth naval museums, recognizing the glory years of the Royal Navy that ruled the seas, and yet the Royal Navy today had less than two dozen destroyers and frigates. It reminded me of an old Rudyard Kipling poem which lamented that “far called, our navies melt away.”

Certainly, in my current professional capacity, I understand the value of museums like those mentioned and teaching our history to the public, but they can too easily be reminders of yesteryear rather than what is needed now and tomorrow. Our country may have grown beyond a symbiotic life with the sea to one of simple indifference, relegated to galleries and exhibits and artifacts.

We as a nation and a navy are not ready because we have chosen not to be. What do we need to prepare for a potential conflict with China?

We need executive vision and action.

We need congressional interest, oversight and funding.

We need a navy to build operational platforms.

We need a much larger industrial base.

We need a public that has a direct relationship to our maritime services that understands they have skin in this Great Game.

We must become ready. But whether or not we are when the time comes, like Cervera, we will do our duty and go with courage regardless of the fate that awaits us.

Is there hope? Certainly.

I see it in an incredibly capable Secretary of the Navy.

I see it with some outstanding admirals.

I see it in the commitment and resiliency of our officers and sailors.

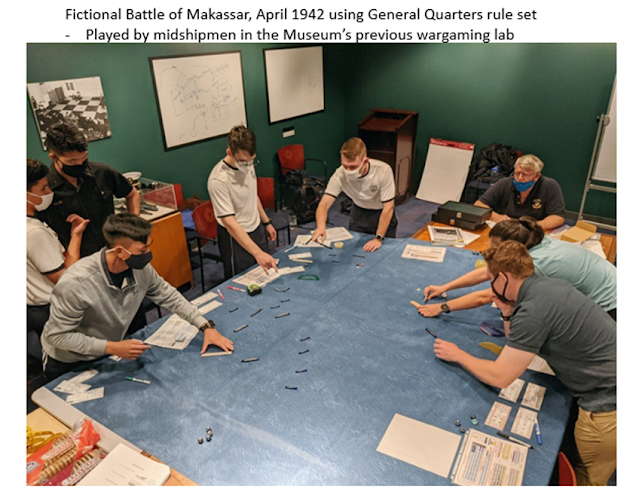

And I see it every day in the creative and energetic midshipmen I teach at the Academy, the future of our naval services.

Thank you.

Claude Berube, PhD, is the author of “On Wide Seas: The US Navy in the Jacksonian Era” and several other books including his third novel, “The Philippine Pact” (2023). He has worked on Capitol Hill, in the defense industry, and the Office of Naval Intelligence. A Commander in the US Navy Reserve, he is currently assigned to a unit with Navy Warfare Development Center. Since 2005 he has taught in the Political Science and History Departments at the US Naval Academy.

No comments:

Post a Comment