Zeebrugge. If you have been there or to its inner city Brugges you know what a beautiful and peaceful place it is - as most all of Belgium is in 2008.

In 1918 though, Belgium was a nightmarish slaughterhouse where the bodies of millions were blended into the beaten earth - where like Okinawa and Iwo Jima over a quarter century later - the living earth would move with a blanked mass of maggots.

In one of history's subtle hints she will give you early if you wish to listen, Britain found herself on the edge of starvation due to a threat few understood or even knew of at the beginning of the war - the submarine. Something new, unexpected and decisive needed to be done.

By 1918, the Great War had entered a decisive phase. While Russia had been knocked out of the war, its place had been taken by the United States, which now provided a fresh pool of manpower and industrial capacity to the Allied cause. The transfer of these resources however was threatened by the continuing war at sea and the U-Boat menace that also threatened Britain's link with the continent. The early advance by the German Army in 1914 had meant that the Belgian ports of Ostend and Zeebrugge had been overrun and with the expansion of the port facilities, the Germans were in a position to threaten the very lifeline that supplied the Allied armies in France. The two ports were connected by a canal network with the city of Brugges that also gave access to the open sea. Brugges in turn, was connected to Germany by the railway network and partially completed U-Boats were shipped from Germany, to be finished at Brugges and then make their way to the open sea by means of the canal system. The canals formed a triangle and inside this, the Germans had built a series of airfields from which they conducted air raids on Britain and fortified the entire length of the coast with light and heavy artillery batteries. The Royal Navy did not attempt to bombard these ports until 12 May 1917 when it bombarded Zeebrugge in order to put the lock system out of action and used a smoke screen to hinder German observation. While the bombard failed in its task, the Germans stepped up defensive measures and as the war progressed, the front line drew ever closer to Ostend, bringing it within range of the Royal Marine heavy howitzer battery in France, forcing the Germans to transfer many of its facilities to Zeebrugge.So, as it is often done in this line of work, the word went out. Volunteer for a mission you have no idea about - odds are you won't come back. You will be trained quickly, sloppily with a pick-up team. You execute.

One of the objectives for the Third Battle of Ypres (Passchendaele) was the expulsion of the Germans from Flanders and to capture the ports of Zeebrugge and Ostend. The battle however failed to achieve the intended breakthrough and so any attempt to expel the Germans from these ports or to deny them the use of these facilities meant that any future attempt would have to made from the sea. The mounting losses in the war at sea caused the Royal Navy to look at the problem. A suggestion by Admiral Keyes that the ports might be blocked by sinking a ship in the entrance was initially rejected but as the war dragged on, the Royal Navy returned to the idea and it was decided that it might be done with the use of several ships, although the exact position would have to be chosen with care so that it would not be possible to get around the ships or to dredge around them to create additional channels and their bottoms would have to be blown to sink them as quickly as possible and prevent drifting.

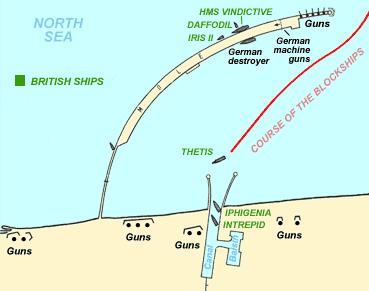

As the ships were approaching the entrance to the port, some protection would be afforded (in the case of Zeebrugge) by the Mole, which extended in an arc across the entrance to the channel. It was over a mile in length and some 100 yards wide, having extensive storage facilities and hangers for seaplanes. A railway connected the Mole to the shore and was used to transfer men, equipment and stores. As the planning for the operation got underway, a special Royal Marine battalion (mainly volunteer) was formed in February 1918 to eliminate the battery that was situated at the end of the Mole and would threaten the block ships as they approached the canal. Lt Col F E Chichester was appointed to command the battalion but was succeeded by Major B N Elliott. The battalion consisted of a headquarters, a machinegun section, a mortar section, three rifle companies and medical support staff. The troops were to be conveyed to Zeebrugge in HMS Vindictive, assisted by the Iris and the Daffodil, two Mersey ferry boats that had been provided for this operation. Once they had reached Zeebrugge, Daffodil was to push Vindictive against the Mole until she could be secured and disembark the troops. The ships were modified for this task. Special ramps were fitted to Vindictive so that the storming parties could reach the Mole, while Iris and Daffodil had been fitted with ladders to that their parties could climb up onto the Mole. Vindictive was strengthened and armoured against the storm of fire she would receive and additional armament fitted so she could support the troops as the moved onto the Mole.

By April 1918, the preparations for the raid had been completed, the men trained for their tasks and the shipping collected for the operation. Three block ships were to be sunk in the Zeebrugge canal entrance, HMS Thetis, HMS Intrepid and HMS Iphegenia. The first time the force sailed, 11 April 1918, the weather conditions changed as they neared Zeebrugge, which forced a postponement, but on the eve of St George's Day, 22 April 1918 the force sailed and during the passage, Admiral Keyes signalled "St George for England". Commander Carpenter on the Vindictive replied, "May we give the dragon's tail a damned good twist." By 23.20 on 22 April, the monitors had opened fire on Zeebrugge. Twenty minutes later, the motor launches that had accompanied the force began to make the smoke screen. One minute after midnight, St George's Day, Vindictive arrived alongside the Mole after which Daffodil arrived alongside her to push her against the Mole. By this point the smoke screen had begun to lift and the defensive fire was intense. In the approach to the Mole, many of the ramps fitted to Vindictive were damaged and only two could be used to allow the storming parties to disembark on the Mole. The ladders fitted to Iris were damaged as well and so the troops had to transfer to Vindictive to land. Once on top of the Mole, they had to endure intense German machinegun fire in order to get to the battery and while they failed to knock it out, they prevented it from firing on the blocking ships and so succeeded in their mission, something for which they suffered heavy casualties for.

The distraction caused by the motor launches and Royal Marines enabled the block ships to approach the canal entrance without too much difficulty. Thetis ran into problems when one of its propellers got caught in a net, forcing her to collide with the bank. She had to be sunk some distance from the entrance but performed admirable work in helping to direct the remaining two ships into the canal entrance itself. Both Intrepid and Iphigenia were able to be sunk in the correct positions, thus blocking the canal. Two submarines, C1 and C3 were packed with explosives and rammed into the viaduct, demolishing it, thus isolating the Mole from the shore. The crews from the submarines and the block ships were picked up by the motor launches despite heavy fire from the German batteries. By 00.50 on 23 April the recall had sounded and by 01.00 the survivors were all aboard. A quarter of an hour later, Vindictive had cleared the protection of the Mole and was undergoing intensive fire from the Germans but managed to come through it. The raid on Ostend at the same time proved to be a failure but another attempt was tried the next month and Vindictive was used as a block ship in that operation. The Royal Marines had been on the Mole for just an hour and the force had displayed such courage and devotion to duty that it gave great encouragement to the Allied forces at such a dark hour in the war. The 4th Royal Marine Battalion was awarded two Victoria Crosses with another six being awarded for the action at Zeebrugge and three being awarded for the actions at Ostend. At Deal, on 26 April 1918, a ballot was held as to who should receive the awards, with Captain Bamford and Sergeant Finch winning. In order that the gallantry of the battalion would be remembered, it was decided that no other marine battalion should be named the 4th.

In a day where entire nations ponder abandoning the battle against an existential threat to their very existence due to a number of casualties suffered at Zeebrugge in a matter of minutes, it can make you wonder if we can even try to understand what these men did and why. We can try. That is what the study of history is. That is why what we have done to the study of history from elementary school through college and as adults is a crime in itself and a shame on our culture.

In a day where entire nations ponder abandoning the battle against an existential threat to their very existence due to a number of casualties suffered at Zeebrugge in a matter of minutes, it can make you wonder if we can even try to understand what these men did and why. We can try. That is what the study of history is. That is why what we have done to the study of history from elementary school through college and as adults is a crime in itself and a shame on our culture.And

Much was made of the raid. Keyes was knighted, and 11 Victoria Crosses were awarded. The Germans, however, made a new channel round the two ships, and within two days their submarines were able to transit Zeebrugge. Destroyers were able to do so by mid-May.Did it make a difference? Of course it did. Did the pundits of the day nit-pic it to death? No, they understood that war from the Strategic to the Tactical is a dark room you step in to. No, it has only been nit-pic'd once the pundits were safely behind the wall of freedom that those who bled built.

First posted NOV08.

No comments:

Post a Comment