So, I guess the NYT will admit now that what many of us have been saying for a long time is true - the Leftist Diktat of College is a Boomer Let tyranny of the mind. Nawwww ... but there is good news on that front. Gen X and Gen Y are taking academia back, bit by bit, as the campus radical Boomers head to the great commune's waiting room.

When Michael Olneck was standing, arms linked with other protesters, singing “We Shall Not Be Moved” in front of Columbia University’s library in 1968, Sara Goldrick-Rab had not yet been born.I'm a bit skeptical, but this will be a long march. It took 40 years for the tide to fall - it will take longer for it to rise.

When he won tenure at the University of Wisconsin here in 1980, she was 3. And in January, when he retires at 62, Ms. Goldrick-Rab will be just across the hall, working to earn a permanent spot on the same faculty from which he is departing.

Together, these Midwestern academics, one leaving the professoriate and another working her way up, are part of a vast generational change that is likely to profoundly alter the culture at American universities and colleges over the next decade.

Baby boomers, hired in large numbers during a huge expansion in higher education that continued into the ’70s, are being replaced by younger professors who many of the nearly 50 academics interviewed by The New York Times believe are different from their predecessors — less ideologically polarized and more politically moderate.

“There’s definitely something happening,” said Peter W. Wood, executive director of the National Association of Scholars, which was created in 1987 to counter attacks on Western culture and values. “I hear from quite a few faculty members and graduate students from around the country. They are not really interested in fighting the battles that have been fought over the last 20 years.”

Individual colleges and organizations like the American Association of University Professors are already bracing for what has been labeled the graying of the faculty. More than 54 percent of full-time faculty members in the United States were older than 50 in 2005, compared with 22.5 percent in 1969. How many will actually retire in the next decade or so depends on personal preferences and health, as well as how their pensions fare in the financial markets.

Yet already there are signs that the intense passions and polemics that roiled campuses during the past couple of decades have begun to fade. At Stanford a divided anthropology department reunited last year after a bitter split in 1998 broke it into two entities, one focusing on culture, the other on biology. At Amherst, where military recruiters were kicked out in 1987, students crammed into a lecture hall this year to listen as alumni who served in Iraq urged them to join the military.

In general, information on professors’ political and ideological leanings tends to be scarce. But a new study of the social and political views of American professors by Neil Gross at the University of British Columbia and Solon Simmons at George Mason University found that the notion of a generational divide is more than a glancing impression. “Self-described liberals are most common within the ranks of those professors aged 50-64, who were teenagers or young adults in the 1960s,” they wrote, making up just under 50 percent. At the same time, the youngest group, ages 26 to 35, contains the highest percentage of moderates, some 60 percent, and the lowest percentage of liberals, just under a third.

When it comes to those who consider themselves “liberal activists,” 17.2 percent of the 50-64 age group take up the banner compared with only 1.3 percent of professors 35 and younger.

“These findings with regard to age provide further support for the idea that, in recent years, the trend has been toward increasing moderatism,” the study says.

...

When Mr. Olneck earned his degree, traditional views of American education were also being upended. Radical revisionists ridiculed the view of public education as a beneficent democratic project. They raised questions about equal access, how schools reinforced class differences, and whether social science should, or even could be free of ideology.

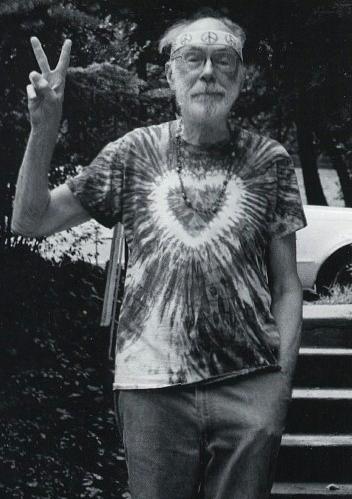

At the start of his career, Mr. Olneck traced the links between where someone’s family came from and where they ended up on the economic and social ladder. Although he has done quantitative research, 20 years ago he jettisoned number-centric studies for historical narrative, exploring how schools throughout the 20th century responded to immigrants and diversity. In his work one can detect some of the era’s preoccupations when he argues, for instance, that fights over bilingualism and standard English were about power.

The same goes for his extracurricular activities. In 1989 he worked to kick the R.O.T.C. off campus because of the Defense Department’s ban on homosexuals. (The effort failed.) More recently, his neighborhood was riled by a Walgreens plan to open a drugstore. “All these people who had protested the war and civil rights,” Mr. Olneck said, laughing; Walgreens “didn’t know what hit ’em.”

Last fall, he taught Race, Ethnicity and Inequality in American Education, which he introduces in the syllabus: “Schools in the United States promise equal opportunity. They have not kept that promise. In this course, we will try to find out why.” Like many sociologists and education researchers, Mr. Olneck said that today both the kinds of analyses and the theories that prevailed when he was in college have changed. Overarching narratives, societal critiques and clarion calls for change — of the capitalist system or the social structure — have gone out of style. Today, with advances in statistical methods, many sociologists have moved to model themselves on clinical researchers with large, randomized experiments as their gold standard. In their eyes, this more scientific approach is less explicitly ideological than other kinds of research.

Ms. Goldrick-Rab has embraced such experiments. A graduate course she created — partly based on her research of community colleges — focused on “educational opportunity and inequality” at community colleges, with an “emphasis on the critical evaluation and assessment of current up-to-date research.”

Another Wisconsin professor, Erik Olin Wright, a 61-year-old sociologist and a Marxist theorist, described it this way: “There has been some shift away from grand frameworks to more focused empirical questions.”

As for his own approach, Mr. Wright said, “in the late ’60s and ’70s, the Marxist impulse was central for those interested in social justice.” Now it resides at the margins.

...

But as scholars across fields argue, the historical era in which a generation develops — the Depression, wartime or peaceful affluence — is a defining moment for its members. “My generational paradigm is the end of the cold war,” said Matthew Woessner, a 35-year-old conservative and political scientist at Penn State Harrisburg. He and his wife, April Kelly-Woessner, a political scientist at nearby Elizabethtown College who is a year younger and a moderate, have been analyzing faculty survey responses for a new book. The notion that campuses are naturally radical or the birthplace of social movements, Ms. Kelly-Woessner said, was specific to the 1960s and ’70s. “I think the younger generation does look at it differently.”

No comments:

Post a Comment